Sistrurus catenatus (Rafinesque, 1818)

VENOMOUS VENOMOUS VENOMOUS VENOMOUS VENOMOUS

Key Characters: Nine large symmetrical plates on top of head; elliptical pupil; pit between eye and nostril; light-edged dark “bow tie” shaped blotches on back (Fig. 1) and 2 or 3 rows of smaller, round blotches on the sides; rattle or horny button on tail tip; 4 head stripes; back scales strongly keeled; anal plate not divided.

Similar Species: Timber rattlesnake, fox snake. No other Illinois snake has the combination of a rattle and nine symmetrical plates on the top of the head. However, the condition of the head plates can be difficult to see on a live specimen and it is not recommended to get close enough to do so, as this is a venomous species. In addition, because rattle segments can break and very young snakes have an inconspicuous rattle (Fig. 2), it is not always feasible to rely on the rattle. Other characteristics that can be used to distinguish the massasauga from similar species include the dorsal pattern and the color of the tail. The timber rattlesnake, Crotalus horridus, has dorsal blotches that are usually uniform in width across the back (not wider at the edges, or “bow tie” shaped as in the massasauga) and very narrow, sometimes approaching a chevron. The timber rattlesnake also has a uniformly black tail, whereas the massasauga has 4 to 7 black rings on the tail. The fox snake, Pantherophis vulpinus, has rounder dorsal blotches (again, not “bow tie” shaped) and only one row of smaller blotches on each side. Here is information related to the differences between a massasauga and a fox snake. One final comment concerning the identification of a massasauga; this species is very rare in Illinois, currently restricted to perhaps only one location in Illinois, in Clinton County. Therefore, the probability that you will see a massasauga in Illinois is very low. See the Key to Snakes of Illinois for help with identification.

Subspecies: Three subspecies were formerly recognized, with the Eastern massasauga, S. c. catenatus, inhabiting Illinois. However, recent data using molecular markers (Kubatko, et al. 2011. Syst Biol 60(4):393-409) indicate strong support for elevating S. c. catenatus to full species. Because the type locality of Crotalinus (=Sistrurus) catenatus Rafinesque is vague: “the prairies of the Upper Missouri” (Rafinesque, C. S. 1818. American Monthly Magazine and Critical Revue 4:39–42), Holycross et al. (2008, Copeia, 2008(2):421-424) restricted the type locality to “floodplain of the Missouri River, between the mouth of the Platte River and Nebraska City, Nebraska” based on careful review of notes and correspondence of the collector, “Mr. Bradbury”. This places the type locality of S. c. catenatus within the range of the western subspecies, S. c. tergeminus (Say, 1823) and requires a new name to be proposed for the eastern form. Holycross et al. (2008) discuss available names and the issues surrounding giving the eastern form an unfamiliar name.

Description (adapted from Smith, 1961): A moderate-sized (up to 100 cm TL), stout-bodied rattlesnake with 24 to 27 anterior and 19 or 19 posterior rows of strongly keeled scales; ventrals 138 to 151; caudals 22 to 31, the last few of which may be divided; a rattle, or, in juvenile, a large “button” on tip of tail; supralabials 11 to 13 per side; infralabials 12 to 14 per side; top of head with 9 enlarged symmetrical plates; a pit present between eye and nostril on each side of head; groundcolor above, gray or light brown, with 29 to 40 middorsal light-edged, dark blotches that may be round or “bow tie” shaped (i.e., concave anterior and/or posterior border). Adjacent blotches may be fused. Each side of body with 3 or 3 rows of alternating round dark spots; tail with 4 to 7 dark rings; venter heavily mottled with black; narrow, but distinct light stripe extending from pit to angle of jaws on each side of head; top of head with a pair of dark bars or stripes extending from the parietal onto the neck. Newborn tail tip yellow (Fig. 2), but darkens with age.

Habitat: Old fields, floodplain forests, marshlands, and bogs.

Natural History: Active March through October, often suns on clumps of grass, in branches of small shrubs, or near crayfish burrows. Feeds mainly on small rodents, but Smith (1961) reported a captive adult fed on small snakes, frogs, and mice. Shepard et al. (2004. Am. Midl. Nat. 152:360–368) examined diet and prey preference of neonate Eastern Massasaugas from Clinton County, Illinois. Prey recovered from free-ranging neonates consisted primarily of southern short-tailed shrews (Blarina carolinensis). In feeding trials, neonates demonstrated a preference for snake prey, disinterest in anuran and insect prey and indifference toward mammalian prey. Breeds spring and autumn with 4–20 young born late summer or early autumn. Newborn 20–30 cm TL. Main predators are hawks, predatory mammals, and other snakes.

Pathogens and Toxins. Several recent studies of overall health and pathogens have been conducted on massasaugas in Clinton County, IL. Allender et al. (2006, Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 42(1), pp. 107–114) collected baseline complete blood count and plasma biochemistry data and to assess the prevalence of antibodies to West Nile virus (WNV) and ophidian paramyxovirus (OPMV). None of the snakes tested (n=21) were seropositive for WNV, whereas all (n=20) were seropositive for OPMV. Allender et al. (2011, Emerging Infectious Diseases, 17, 12) documented a keratinophilic fungal infection caused by Chrysosporium sp. in three free-ranging massasaugas from Clinton County, IL that presented with severe facial swelling and disfiguration. All three snakes died three weeks after discovery of the infection. A fourth snake presented with the same symptons and was treated with thermal and nutritional support and antifungals, but died within one year. In a follow-up study Allender et al. (2013, Copeia 2013, (1): 97–102) conducted polymerase chain reaction assays from swabs collected from the faces of 34 snakes at the same study site. There was no evidence of Chrysosporium in any of the samples and none of the snakes showed clinical signs or fungal dermatitis.

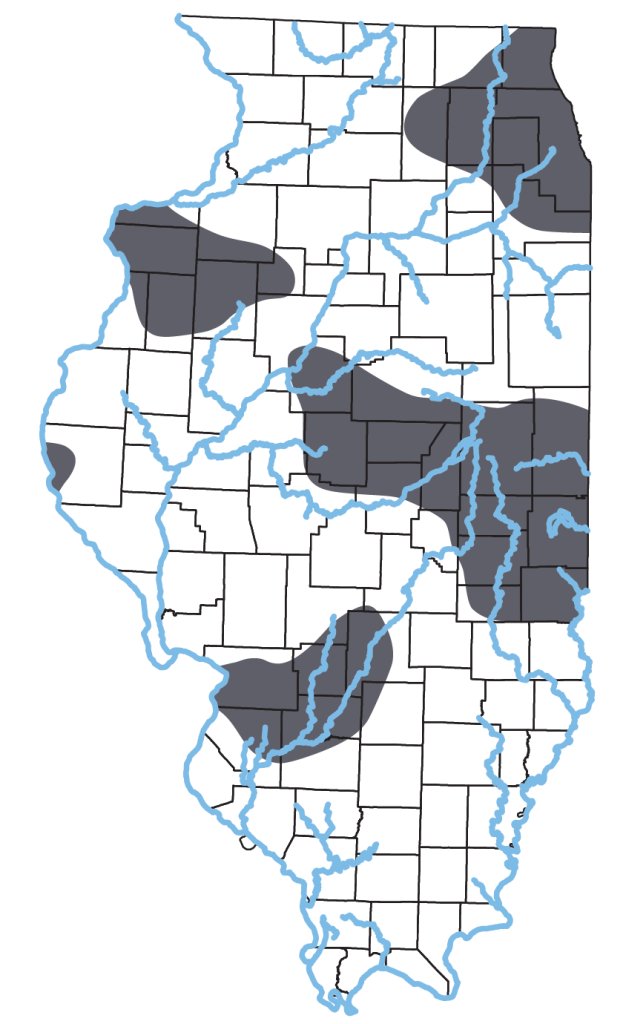

Distribution Notes: Formerly common over northern two-thirds of the state, prior to drainage of prairie marshes and intensive agriculture. Smith (1961) mapped 25 occurrences from 20 counties. Three of these occurrences (Hancock, Cumberland, and Crawford counties) were mapped as black dots which signifies Smith examined a specimen. I am unable to locate any specimens from those counties. There are unvouchered records for Cumberland County that are valid so it is plotted. The Hancock and Crawford records are not plotted. The Hancock County specimen may have been from Carthage College as this institution is acknowledged in Smith (1961) as one that made their holdings available to him. Smith plotted an open dot (reliable literature record) in Jackson County that was based on a record in Gloyd (1940. The rattlesnakes, genera Sistrurus and Crotalus. Chicago Academy of Science Special Publication 4) listed as “FMNH 18657”. This specimen is actually a Crotalus horridus. The Peoria and McLean County records (open circles) on Smith’s map are from Garman (1892. A synopsis of the reptiles and amphibians of Illinois. Illinois Laboratory of Natural History Bulletin 3(13):215-388), but many of Garman’s records are suspect so they are not plotted here. The other open circle record from Smith’s map that is rejected is that from Coles County, which is based on a report by Hankinson (1917. Amphibians and reptiles of the Charleston region. Illinois State Acad. Sci. Trans. 10:322-330). Hankinson did not report seeing a specimen from Coles County, only that “Reports by old residents of the many rattlesnakes that lived about these places are common. These were probably Prairie Rattlers, Sistrurus catenatus.” Today only one population exists in Illinois, that in Clinton County. Ironically, Smith (1961) was not aware of the existence of the Massasauga in Clinton County. Smith (1961) was also apparently unaware of the museum records for the Massasauga from Adams, Logan, Mercer, Stark, and Warren counties. Vermilion County is shaded based on a letter I received from a farmer who recalled seeing them near his home prior to the 1960s. A follow-up conversation convinced me of the validity of this occurrence.

Status: Endangered in Illinois.

Etymology: Sistrurus – sistrum (Latin) meaning ‘a rattle’; catenatus – catena (Latin) meaning chain; atus (Latin) meaning ‘having the nature of’, ‘pertaining to’.

Original Description: Rafinesque, C.S. 1818. Further account of discoveries in natural history, in the western states. American Monthly Magazine and Critical Review. 4(1):39-42.

Type Specimen: Not designated, but see the section on subspecies above.

Type Locality: “the prairies of the Upper Missouri” Recently restricted to “floodplain of the Missouri River, between the mouth of the Platte River and Nebraska City, Nebraska” by Holycross et al. (2011). See the section on subspecies, above for more details.

Original Name: Crotalinus catenatus Rafinesque, 1818.

Nomenclatural History: Kennicott (1855) used the name Crotalophorus kirtlandii Holbrook, 1842, a junior synonym and Davis & Rice (1883) used Caudisona tergemina (Say, 1823), the latter illustrating the confusion surrounding the ranges of the subspecies recognized at that time.